The Five Elements of Spirit

Yin Yoga and the felt language of alchemy

This week’s essay explores the Five Elements of Spirit through the fascia, the breath, and the emotional terrain of Yin Yoga. We look at how Spirit doesn’t arrive through effort, but through restoring the ground of perception—physically, energetically, emotionally.

If this work speaks to you, I invite you to join the Yin Practice Membership—weekly live classes, an ever-growing library of replays, and a deep dive into how Chinese Medicine, contemplative practice, and functional anatomy come alive through the Yin Yoga practice.

It’s not just a class. It’s a weekly rhythm for realignment, reflection, and remembering.

We often hear that Yin Yoga is slow, soft, or passive. But make no mistake: this practice is not idle. It is a medicine of re-patterning. When we come into stillness and sustain it with attention, something begins to shift. Subtly, and then not so subtly, the body begins to re-organize itself.

Fascia—the body’s connective tissue system—is the terrain where this alchemy unfolds. It wraps, weaves, and permeates every cell and organ in the body. Once considered inert packing material, fascia is now recognized in modern research as a sensory organ, an electrical conductor, a medium for communication and coordination across the whole system.

But fascia is vulnerable. Under chronic stress, emotional contraction, or trauma, the fluid nature of fascia begins to dry. It becomes disorganized. Its collagen fibers stick together in a phenomenon called crosslinking—like Velcro mats that were meant to glide. Adhesions form. Mobility decreases. And most importantly: information flow becomes impaired.

As Robert Schleip, one of the leading researchers in the field, has shown, fascia is highly innervated and sensitive. When its organization falters, not only does movement become painful, but perception itself becomes distorted. We feel less. We freeze. We brace. We disconnect.

Qi as Organizational Intelligence

This is where Chinese Medicine enters with startling resonance. In the classical model, Qi is life force. But Dr. Daniel Keown, a Western physician and Chinese Medicine practitioner, offers a compelling definition: Qi is organizational intelligence. It is the wisdom of form, flow, and function. It’s not a mystical energy, but a description of how life arranges itself toward harmony.

And the fascia, he says, is the meta-tissue that carries this intelligence. When fascia is healthy—well-hydrated, well-organized—Qi flows. The body communicates. Healing becomes possible. But when the fascia is tangled or dry, Qi gets stuck. Symptoms arise. Emotions stagnate. We lose our capacity to perceive clearly.

Yin Yoga, practiced with attention and care, helps restore the internal environment. We don’t force change; we make room for change. The long-held postures apply gentle stress to the connective tissue, awakening the cells, stimulating hydration, and inviting reorganization. As tissues rehydrate and glide, information flows. Not just neural signals, but emotional and energetic signals as well. The breath softens. The nervous system unwinds. And the spirit—whatever form it takes in that moment—can begin to circulate.

The Emotional Equivalent

This physiological story has an emotional mirror.

In trauma theory, a common insight is that traumatic experiences fixate us in time. They bind our responses. Certain feelings—fear, rage, grief, shame—become frozen patterns. And many of us may carry the subtle belief that these patterns are a sign of spiritual failure. That we should be over it. That if we breathe more deeply, or align our chakras, or do our mindfulness properly, we can eliminate these disturbances.

But this view, I believe, enacts a kind of internal violence.

As I wrote recently, mindfulness can sometimes become a tool of suppression—a well-intentioned method for disavowing the very parts of us that need presence the most. The real medicine is not suppression, but relational connection.

If Qi is spirit’s intelligence, and fascia is its medium, then the healing lies not in perfecting our minds, but in cultivating the ground through which perception flows. The breath becomes a tide that softens the tissue. The posture becomes a crucible that holds the process. The attention becomes a witness that allows without control.

And slowly, we come to realize that the so-called negative emotions are not errors. They are communications. They are signals from the intelligence within. As Jack Engler has observed, even advanced meditators do not necessarily experience fewer afflictive emotions. What changes is their relationship to those emotions—their capacity to receive them without being overrun.

This is the alchemy of yielding. The transformative intelligence of not fighting what arises. The trust that Spirit knows how to move through us, if given the space.

The Five Elements of Spirit

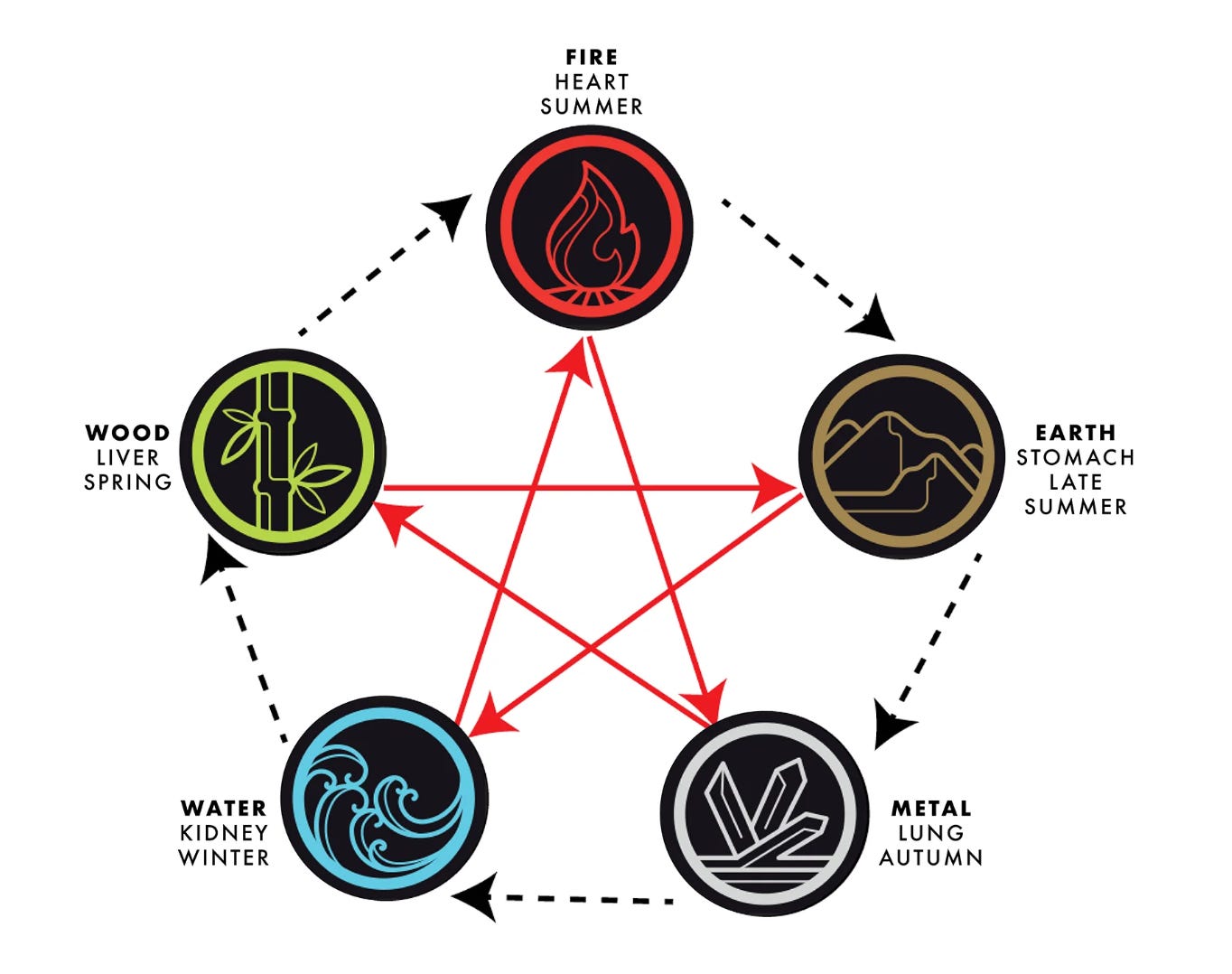

Over time, I’ve come to appreciate the Five Elements of Chinese Medicine not just as a theory of health or personality, but as a living grammar of experience—an internal weather system that expresses itself through sensation, mood, memory, and breath. For those unfamiliar with the system, the Five Elements—Metal, Water, Wood, Fire, and Earth—are each associated with a season, an organ, and a core emotional tone. But what interests me most is how they show up, not as metaphors, but as felt intelligences that I learn to recognize more clearly through practice.

This recognition doesn’t come through analysis or symbolic mapping. It emerges through somatic familiarity, through staying present at the edge of what I can feel without retreating or flooding. Each Element carries signals—tensions, sensations, urges—that make themselves known within a tolerable range. Not as abstractions, but as embodied insight.

Metal, for example, often comes forward as a tightening and release in the breath. When I settle into stillness, I sometimes notice a sensation around the lungs—a soft ache, a thinning, a grief that’s neither memory nor narrative but something textured and real. If I stay with it gently, something begins to exhale. Not always, and not fully. But enough to feel the body letting go of what it no longer needs.

Water lives lower, nearer the base. I often experience it as a quiet vigilance—a low hum of readiness that softens only when I feel secure enough in my surroundings. Sometimes, in postures that open the lower back or inner thighs, there’s a hesitation—not pain, but a pause—that carries the question: Is this safe? And if I meet it with patience rather than pressure, the signal changes. The body doesn’t need to be convinced. It just needs to be heard.

Wood arises more sharply—a pulse of agitation or frustration, sometimes surfacing mid-pose. It shows up when I’ve lingered too long, or when something in me wants to move, to assert, to adjust. Earlier in my practice life, I might have interpreted that impulse as resistance to be subdued. Now, I listen more closely. Wood’s signal isn’t always telling me to move—but it is telling me something wants to grow, and growth often begins in friction.

Fire is different. It’s less about arousal and more about presence. In Chinese Medicine, Fire governs the Heart and the spirit called Shen—often translated as consciousness, clarity, or joy. But as Giovanni Maciocia pointed out, joy can also become overstimulation. Too much Fire scatters the Heart. I’ve known this—especially after long teaching days or post-retreat highs—when my system feels ungrounded and buzzy, disconnected from depth. But there are other times, quiet and subtle, when I sense a warmth in the chest, an ease in the breath, a gentle widening of awareness. That’s Fire, too. Not the blaze of excitement, but the glow of coherence.

And Earth, the element of digestion and integration, seems to speak last—after the posture, in the space between doing and reflecting. I sometimes notice that I’m trying to extract meaning too soon, to interpret or label what I’ve felt. Earth reminds me to pause, to let the body process on its own terms. To trust that the psyche, like the gut, knows how to metabolize when given time and space.

These aren’t performances. I don’t try to feel them. I only try to stay close to what’s present, to listen without agenda. The Elements don’t speak in English or theory—they speak in pressure and release, in temperature and texture, in breath and boundary. And through this ongoing dialogue, I come to recognize Spirit not as something outside myself, but as the quality of attention that arises when I stop trying to fix or transcend what’s here.

Each practice becomes a kind of translation. And over time, I learn to trust the language of sensation, the wisdom of the body, and the presence that lives underneath it all.

The Return of Wholeness

Yin Yoga is not a cure. It’s a context—a space in which organization can be restored, both in body and in psyche. Within this context, energy can circulate, perception can clarify, and the living intelligence of Spirit can remember itself.

To practice in this way is to trust the process of reorganization—to let the body’s quiet intelligence lead the way home.

With care,

Josh

If you’d like to explore these themes more deeply in your own practice, the Yin Practice Membership offers weekly live sessions, a rich library of replays, and a gentle path through the Five Elements, fascia, and contemplative reflection. You are warmly welcome.